International Political Economy

International political economy is about the economics of international politics and the politics of international economic choices and relationships. This was one of my first areas of research. I wrote a m aster’s t hesis at the University of Chicago on norms of i nternational debt collection enforcement in the 19 th century, and then moved into the early 20 th century when I used a Fulbright Scholarship in London to research the founding of the International Bank for Settlements The BIS was founded as a managing institution for privatizing World War I war debts and reparations. That research revealed how active a role private financiers played in moving debts from states to private markets. My PhD dissertation of the same name became my first book, Who Adjusts? Domestic Sources of Foreign Economic Policy During the Interwar Years ( described under the book section of my website )

First unofficial meeting of the Bank for International Settlements, April 1930

Who Adjusts?

My research into international political economy has been very heavily influenced by

the path-breaking research

and

writing of my mentor, Robert Keohane. As a scholar of international cooperation, he

influenced me to ask

questions about

the possibilities for and impediments to international economic cooperation among

states. Who Adjusts? located

at least

part of the answer in domestic politics: the interwar gold standard would not be

credible as long as markets

believed

that the representation of labor interests would inject inflationary pressures into

financial markets. New

domestic

coalitions and configurations made international cooperation by the old rules newly

impossible. Highly

independent central banks

were so concerned with fighting inflation, that they did not contribute to the

international adjustment process.

The politics of monetary policy and capital markets formed the core of my research

for several years. The Post-World War

II years were quite a contrast to the interwar years: international economic

relationships became much more

institutionalized, with the United States at the core of the system, at least for a

few decades. While working for a

year in the Capital Markets Department of the International Monetary Fund, I began

to research monetary (in)stability in

this new setting. One of my articles looked at the importance of multilateral

commitment, contained in Article VIII of

the IMF statutes, for states to keep their current accounts free from restrictions,

and I found that making an explicit

declaration to do so

had an important

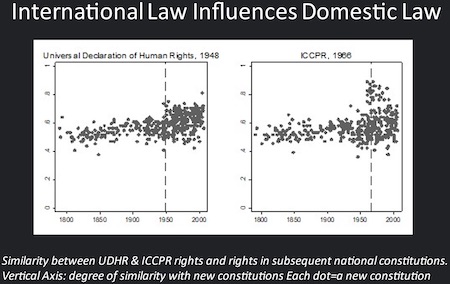

effect on currency openness and stability. This research began to spark my interest

in the possible constraining

power of international law.

Another project in this phase included a theory of financial market regulatory harmonization

.

This research compared different kinds of regulations – for prudential capital in

banks, for international accounting

practices, for securities disclosures, and anti-money laundering – and argue that in

some cases markets encouraged

convergence, but in other cases (especially anti-money laundering) they did not.

International institutions such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and

the World Trade Organization have

played a significant role in structuring international economic relationships over

the past 75 years. These institutions

have rules and procedures for trade dispute settlement, which raises issues about

who uses them, and to what ends?

Research with Andrew Guzman focused on trade dispute settlement shows that

escalation to a full-blown legal panel in the

WTO depends on the divisibility of the issue at stake.

Moreover, we found good evidence in dispute patterns

that poor states appear to lack the financial, human, and institutional capital to

participate fully in the dispute

resolution system.

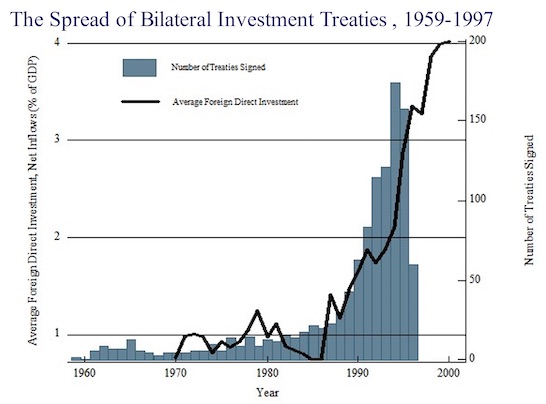

Finally, I have researched the liberalization and especially the protection of the

interests of foreign direct

investors. As discussed under my diffusion research, one of my major research findings, with Elkins and Guzman,

is that competitive pressures have given rise to the spread of bilateral treaties

among states that commit to standards

of investment protection and dispute settlement. I have also explored the

consequences of the spread of bilateral

investment treaties globally and in East Asia. World-wide, capital importing states

tend to sign investor protections in

this form when they face recession,

which affects their negotiating position and the substance of the commitments they

make (to the advantage of investors

rather than states). The pattern is not quite the same in East Asia,

where states have adopted

BITs when their economies were growing robustly. These articles demonstrate the

political context for BITs negotiations,

and suggest some possible criticisms of the nature and spread of investment dispute

settlement.